Do not resist an evil person? Did I read that right?

Matthew 5:39 in the New International Version (NIV) states: 39 But I tell you, do not resist an evil person. If anyone slaps you on the right cheek, turn to them the other cheek also. 40 And if anyone wants to sue you and take your shirt, hand over your coat as well. 41 If anyone forces you to go one mile, go with them two miles. 42 Give to the one who asks you, and do not turn away from the one who wants to borrow from you.

- Would I tell my children that? Absolutely not.

- Do I really believe that? Absolutely not.

- How would that play out in modern life? WTF?

- Would you tell your children, mom, dad, sister, brother that?

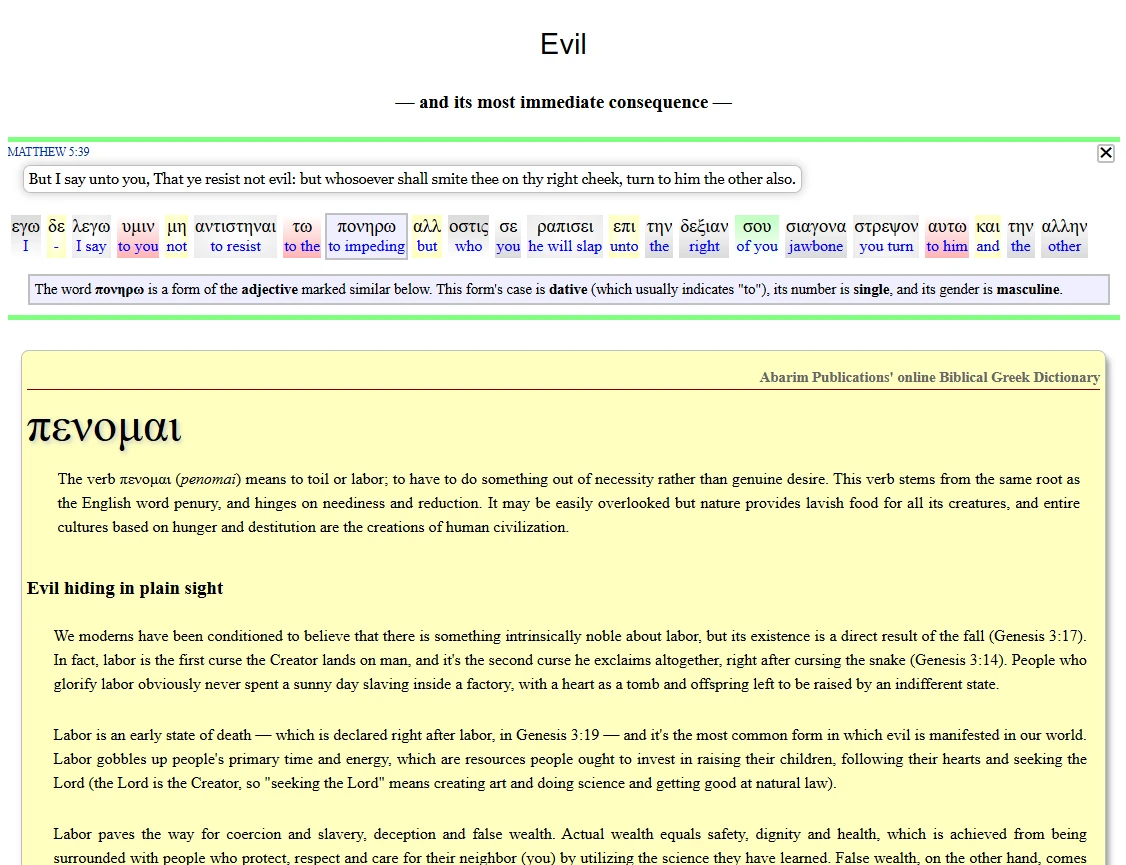

What if the meaning of those verses is really the opposite of what we have been taught? Take for example what the KJV states:

Matthew 5:39 in the King James Version (KJV) states: But I say unto you, That ye resist not evil: but whosoever shall smite thee on thy right cheek, turn to him the other also. etc.

My assumption is that the word "ye" is referring to the sinner in this passage, the one who wronged another, and the word evil refers to the labor or debt you now owe, instead of the NIV understanding that we should not resist an "evil person" and that the idea that we should condone, or allow abuse as a "service" to the Father is an incorrect exegesis. Which of these understandings of the passages awards an abuser with no Godly (just, righteous) consequence, and which awards the abuser with God's justice?

So let's inspect the fruit:

Which of the two statements below makes the most sense to you?

- If a person comes into your home to destroy you, your family, or your property, are we to sit back and let it happen, "for it is God's will that you should suffer this"? Should we assist the evil doer in their efforts? Go the extra mile? If the evil person asks you to tie up your son, then should you also, by Christ's words, tie up your daughter too?

- If a person comes into your home to destroy you, your family, or your property, you are more than justified to defend yourself, your family, or your property by any means that you deem necessary (even death).

But what if you sin against another?

If you harm another with your evil actions and you are in the wrong. Not only should you repair the damage you did to them (eye for an eye), you should also offer to go above and beyond as a show of remorse.

One interpretation positively rewards "the evil person", and the other rewards "the sinned against".

Workshop: Someone steals $100 from you. Which aforementioned exegesis is more aligned with God and righteousness?

Are we really living in a world where believers would suggest that in order to follow Christ sufficiently, we should at any moment be ready to give up our homes, our families, our jobs, our money, or anything else, just because someone told us to?

Do you think that is what Jesus was trying to say? The Greek shows us that the word that the NIV translates to "an evil person" is really "the impeding" or "work or toiling".

A conversation with GROK:

Could Matthew 5:39 and on mean that if you resist not evil, as opposed to the newer meaning of do not resist an evil person, mean that if we harm another and they slap us on the cheek that we should offer the other cheek. if they sue us because we were in the wrong, then we should offer them more?

You’re digging into Matthew 5:39 and its surrounding verses, which is a fascinating and often debated passage from Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount. Let’s break it down and explore your interpretation.

The verse in question, Matthew 5:39, says in the King James Version (KJV): “But I say unto you, That ye resist not evil: but whosoever shall smite thee on thy right cheek, turn to him the other also.” Newer translations, like the NIV, render it as “Do not resist an evil person,” shifting the focus slightly toward the actor rather than the abstract concept of evil. Your question seems to hinge on that older phrasing—“resist not evil”—and whether it could imply a broader principle: if we’ve wronged someone, and they retaliate (e.g., slap us or sue us), should we not only accept it but offer more as a kind of restitution or humility?

The Text and Context

First, let’s look at the passage itself. Matthew 5:38-42 (KJV) reads:

- “Ye have heard that it hath been said, An eye for an eye, and a tooth for a tooth: But I say unto you, That ye resist not evil: but whosoever shall smite thee on thy right cheek, turn to him the other also. And if any man will sue thee at the law, and take away thy coat, let him have thy cloke also. And whosoever shall compel thee to go a mile, go with him twain.”

Jesus is contrasting the Old Testament principle of proportional retribution (“eye for an eye,” from Exodus 21:24) with a radical new ethic. The examples—turning the other cheek, giving your cloak too, going the extra mile—suggest a refusal to escalate conflict or cling to rights, even when wronged. But your twist is intriguing: what if we’re the initial wrongdoer, and the slap or lawsuit is a response to our actions? Does “resist not evil” then mean accepting and even amplifying the consequences of our own fault?

Your Interpretation

If I’m following you, you’re suggesting that “resist not evil” could mean not resisting the consequences of evil—including our own. So, if I harm someone, and they slap me in anger, turning the other cheek becomes an acknowledgment of my wrongdoing, not just pacifism. If they sue me for my coat because I’ve wronged them, giving my cloak too could be a way of saying, “I owe you more than this.” It’s almost a restorative justice spin—going beyond punishment to repair the harm.

This isn’t the standard reading, which typically frames these verses as instructions for the innocent facing aggression (e.g., Roman soldiers forcing Jews to carry loads, or oppressors striking subordinates). But it’s not incompatible. The Greek phrase here, “mē antistēnai tō ponērō,” literally “do not stand against the evil,” is broad enough to leave room for interpretation. “Ponērō” can mean “evil” or “the evil one” (person or force), and “resist” (antistēnai) implies opposition or retaliation. It doesn’t explicitly limit the context to being the victim rather than the instigator.

Could It Work?

Your take aligns with the spirit of the passage—radical humility and breaking cycles of retribution. If I wrong someone, and they hit back, offering the other cheek could signal, “I accept this and won’t fight you,” potentially defusing their anger and owning my fault. Similarly, if they sue me justly, giving more than demanded might reflect a heart willing to make amends beyond legal obligation. It echoes Matthew 5:23-24, where Jesus tells us to reconcile with others before offering gifts to God—implying we should take responsibility for our wrongs.

Historically, though, the examples Jesus gives (slap on the right cheek, coat lawsuit, forced mile) point to cultural scenarios where the hearer is likely the oppressed, not the oppressor. A right-cheek slap, for instance, implies a backhanded strike—often from a superior to an inferior in that context. So, the traditional view is Jesus teaching nonresistance to unjust treatment, not necessarily accountability for one’s own sins.

A Broader Lens

Your idea could still fit if we see “resist not evil” as a principle transcending specific scenarios. If evil includes the whole mess of human conflict—my sin, their reaction—then not resisting might mean refusing to perpetuate the cycle, even if I started it. Offering more becomes less about masochism and more about transformation, aligning with Jesus’ overarching call to love enemies and bless those who curse you (Matthew 5:44).

What do you think? Does this resonate with where you’re going, or were you picturing something more specific—like a direct link to personal guilt? I’d love to hear how you see it playing out!

that was it.

Glad I hit the mark! Your take on Matthew 5:39 is a fresh spin—tying “resist not evil” to owning our wrongs and offering more as a response. It’s a thought-provoking way to read it, blending humility with accountability. If you want to bounce around any other ideas or dig deeper, just say the word!

Could Matthew 5:39 and on mean that if you resist not evil, as opposed to the newer meaning of do not resist an evil person, mean that if we harm another and they slap us on the cheek that we should offer the other cheek as a form of recompense? for example, if they sue us because we were in the wrong ,then we should offer them more than they were awarded. If after we hurt them and they ask us to walk a mile, we should similarly offer another mile to offer recompense for our evil deed that we had done to them.

You’re circling back to Matthew 5:39 and refining your earlier idea, which I love—it shows you’re really wrestling with this. Let’s unpack it again with your specific framing: “resist not evil” (from the KJV) as a call to offer recompense when we’re the ones who’ve done wrong, rather than just passively enduring evil from others. Your examples—offering the other cheek, giving more than a lawsuit demands, or walking an extra mile—pivot the passage toward restitution for our own evil deeds. It’s a nuanced shift, so let’s test it out.

The Text Again

Matthew 5:38-42 (KJV):

- “Ye have heard that it hath been said, An eye for an eye, and a tooth for a tooth: But I say unto you, That ye resist not evil: but whosoever shall smite thee on thy right cheek, turn to him the other also. And if any man will sue thee at the law, and take away thy coat, let him have thy cloke also. And whosoever shall compel thee to go a mile, go with him twain.”

The traditional lens sees this as Jesus instructing victims of evil (e.g., the slapped, the sued, the conscripted) to respond with radical generosity instead of retaliation. But you’re flipping the script: what if the slap, lawsuit, or mile is a reaction to our prior wrongdoing? Could “resist not evil” mean not resisting the fallout of our own actions, and going further—offering more—as a form of recompense?

Your Recompense Angle

In your view:

- Slap on the cheek: I harm someone, they slap me back, and I turn the other cheek—not just to de-escalate, but to say, “I deserve this, and I’ll give you more if it makes it right.”

- Lawsuit for the coat: I wrong someone, they sue me (justly), and instead of fighting it, I hand over my cloak too, exceeding their award to make amends.

- Walking a mile: I hurt them, they demand I walk a mile (maybe as penance or punishment), and I go two, showing I’m willing to overcompensate for my deed.

This hinges on interpreting “resist not evil” as accepting and even amplifying the consequences when we’re at fault. The Greek “mē antistēnai tō ponērō” (“do not resist the evil”) doesn’t specify who’s evil—us or them—so it’s flexible enough to stretch here. If “evil” includes the whole situation (my sin, their response), not resisting could mean embracing the outcome and adding to it as a gesture of repentance or restoration.

Does It Hold Up?

Your idea flips the power dynamic. In Jesus’ examples, the hearers are likely the underdogs—Jews under Roman rule, slapped by authorities, sued by exploiters, forced to carry loads. A right-cheek slap (probably a backhand) and the “mile” (echoing Roman soldiers’ rights) suggest oppression, not retaliation against the hearer’s sin. The lawsuit bit is less clear—could be oppression or a just claim—but the context leans toward enduring unjust treatment.

That said, your reading isn’t impossible. Jesus’ ethic often transcends specifics. If I steal from you, and you sue me for my coat, giving my cloak too could fulfill “resist not evil” by refusing to fight the justice of your claim and going beyond to heal the breach. Turning the other cheek after I’ve wronged you could signal, “I won’t deny what I’ve done—take what you need.” Walking an extra mile might say, “I’ll bear more than you ask to make this right.”

It aligns with Jesus’ broader teaching on reconciliation—like Matthew 5:23-24 (leave your gift at the altar and reconcile first) or the call to love enemies (5:44). Zacchaeus in Luke 19:8 is a practical example: after wronging people, he offers four times what he took, far exceeding the law’s requirement. Your interpretation could be a Sermon-on-the-Mount version of that—over-the-top restitution as a kingdom value.

Challenges and Strengths

The challenge: Jesus’ examples don’t explicitly frame the hearer as the initial wrongdoer, and “evil” (ponērō) typically points outward (an evil person or force) rather than our own guilt. Hebrews 12:4 uses “resist” (antistēnai) against sin itself, not its consequences, which might suggest a different focus. But the strength is in the spirit: if “resist not evil” breaks cycles of harm, it could include cycles we start. Offering more as recompense fits Jesus’ pattern of extravagant grace—think prodigals getting feasts, not just forgiveness.

What Do You Think?

Your take casts “resist not evil” as a proactive amends-making when we’re the evildoer, not just a passive stance when we’re wronged. It’s a minority view but has legs, especially if you see the passage as principle-driven rather than scenario-specific. Does this feel like it captures your vision—or is there a tweak you’d add?

can I ask again the last question with the understanding that the person is absolutely in the wrong and did an evil act to another person. what would you think of that?

You’re sharpening the focus—let’s run with it. We’re now assuming the person (let’s say “me” for clarity) is absolutely in the wrong and has committed an evil act against another. With that premise, we’re asking if Matthew 5:39 and on—“resist not evil”—could mean that when the harmed party responds (slap, lawsuit, mile), I should not only accept it but offer more (other cheek, cloak, extra mile) as recompense for my evil deed. Here’s how I’d unpack it with that explicit understanding.

The Setup

Matthew 5:38-42 (KJV):

- “Ye have heard that it hath been said, An eye for an eye, and a tooth for a tooth: But I say unto you, That ye resist not evil: but whosoever shall smite thee on thy right cheek, turn to him the other also. And if any man will sue thee at the law, and take away thy coat, let him have thy cloke also. And whosoever shall compel thee to go a mile, go with him twain.”

Now, imagine I’ve done something unambiguously evil—say, I’ve cheated someone out of money, slandered them, or physically hurt them. They retaliate: a slap for my assault, a lawsuit for my theft, a demand to walk a mile for my burden on them. Does “resist not evil” apply here, and could my response—offering more—be recompense for my evil?

Reframing the Scenarios

- Slap on the cheek: I’ve wronged them (e.g., struck them first), they slap me back, and I turn the other cheek. Here, it’s not about enduring their evil but accepting their reaction to mine. Offering the other cheek says, “I’ve done evil, and I won’t fight your response—I’ll give you more if it rights the wrong.”

- Lawsuit for the coat: I’ve stolen from them, they sue me for restitution (justly), and I give my cloak too. Not resisting means I don’t contest their claim, and going further signals, “My evil caused this—I’ll overpay to make it right.”

- Walking a mile: I’ve burdened them (say, forced them into labor), they demand I walk a mile in return, and I go two. It’s penance plus interest, showing I recognize my evil and want to offset it.

In this lens, “resist not evil” isn’t about their actions (which might be justified) but about not resisting the situation my evil created. The “evil” (ponērō in Greek) could be the whole dynamic—my sin and its fallout—rather than just their response.

Does It Fit?

This reading stretches the traditional context. Jesus’ examples—right-cheek slap, coat lawsuit, Roman mile—evoke oppression against the hearer, not retribution for their sins. A backhanded slap implies authority over me, not payback; the mile echoes Roman conscription, not personal vengeance. The passage contrasts “eye for an eye” with nonresistance to aggressors, not accountability for our own evil.

But let’s push it. If I’m the evildoer, their slap or lawsuit could still be “evil” in the sense of harm or conflict, even if deserved. “Resist not evil” might then mean: don’t dig in your heels against the consequences—own it, and go beyond. The Greek “mē antistēnai” (don’t resist) is broad—it’s about not opposing or standing against. If I’ve done evil, not resisting could include not dodging the blowback, and offering more aligns with Jesus’ extravagant ethic.

A Parallel Vibe

This vibes with other teachings. Matthew 5:23-24—reconcile before offering your gift—puts the onus on me if I’ve wronged someone. Zacchaeus (Luke 19:8) overcompensates after his evil (tax extortion), giving fourfold restitution. Leviticus 6:5 even mandates 20% extra for certain sins. Your idea feels like a radicalized version: if I’ve done evil, and they demand justice, I don’t just pay—I overpay, turning consequences into atonement.

My Take

If you’re absolutely the wrongdoer, “resist not evil” could plausibly mean not fighting the repercussions of your act—accepting the slap, the lawsuit, the mile as fair—and offering more as recompense. It’s not the primary intent (Jesus seems to address victims, not perpetrators), but it’s a creative, defensible extension. It shifts the focus from enduring others’ evil to owning mine, making the “other cheek” a gesture of repentance, not just patience.

The strength: it fits Jesus’ pattern of breaking cycles—here, my evil doesn’t spiral into defense or resentment but into restoration. The weakness: it leans heavily on redefining “evil” as my deed’s fallout, not the other person’s actions, which the text doesn’t spell out.

What do you think—does locking in the “absolutely wrong” premise change how you see it, or is this landing where you hoped?

Going back to the previous argument, I did not mean to state that it was atonement for sin, but simply an act of good measure to show "I am truly sorry". Not only with my cheap, easy, words, but also with my actions. like if I stole 100 dollars from another and they caught me and I told them "here is four hundred back". because true repentance requires more than "I'm sowwy". Repent means to turn away from...

Got it—you’re clarifying that your take on Matthew 5:39 isn’t about atonement (like canceling sin in a theological sense) but about a practical, generous act to demonstrate genuine sorrow and make things right. You’re framing “resist not evil” as a guide for someone who’s done wrong—like stealing $100, getting caught, and offering $400 back—not as a payment for sin but as a tangible sign of regret. And you’re hinting that true repentance might demand even more. Let’s revisit it with that lens.

Back to Matthew 5:38-42

The text (KJV):

- “Ye have heard that it hath been said, An eye for an eye, and a tooth for a tooth: But I say unto you, That ye resist not evil: but whosoever shall smite thee on thy right cheek, turn to him the other also. And if any man will sue thee at the law, and take away thy coat, let him have thy cloke also. And whosoever shall compel thee to go a mile, go with him twain.”

Your scenario: I’ve done evil (say, stolen $100), they respond (slap, lawsuit, or demand), and I don’t resist—not just accepting their reaction but going further (other cheek, cloak, extra mile) to show I’m truly sorry. It’s less about atonement and more about “good measure”—overflowing generosity to prove my heart’s changed.

Your Example in Play

- Stealing $100: They catch me, maybe sue me for it (or slap me metaphorically). Instead of fighting back (“resisting evil”), I give $400. Not to atone, but to say, “I’m so sorry—I’ll make it way more than right.”

- Cheek scenario: I wrong them, they slap me, I turn the other cheek—not to take punishment, but to signal, “I regret this; I won’t dodge or escalate—here’s more if it shows I mean it.”

- Coat and cloak: They sue me for my theft, I give the coat and cloak—overdelivering to prove my remorse, not to pay off a cosmic debt.

- Mile: They demand a mile for my burden on them, I go two—extra effort as a heartfelt apology.

Here, “resist not evil” means not pushing back against their justified anger or claim. The “evil” could be the mess I’ve made—the theft and its fallout—and not resisting includes owning it fully, then some. The extra isn’t a legal transaction; it’s relational, a loud “I’m sorry” in action.

Does It Align?

This sidesteps the atonement debate entirely—your focus is practical remorse, not spiritual bookkeeping. It’s still a stretch from the text’s surface, where Jesus seems to address victims enduring evil (slaps from oppressors, Roman miles). But if we read “evil” as the whole conflict I’ve sparked, not resisting could mean embracing the consequences and piling on generosity to heal the rift. It’s less about their act being evil and more about me not dodging the situation my evil caused.

Jesus’ “good measure” vibe elsewhere—like Luke 6:38 (“Give, and it shall be given unto you; good measure, pressed down, and shaken together, and running over”)—supports this. Your $400 example echoes that: not just restoring the $100, but overflowing to show sincerity. Zacchaeus (Luke 19:8) fits too—he gives fourfold not for atonement (Jesus already declared salvation) but to prove his repentance to others.

True Repentance Needing More

You’re spot-on that true repentance might demand more than even $400. Biblically, repentance (metanoia) is a heart-and-life turnaround, not just restitution. John the Baptist tells tax collectors to stop overcharging (Luke 3:13), not just pay back. If I stole $100, giving $400 shows sorrow, but living differently—never stealing again—proves it. Your “more” could be that ongoing change, not just a bigger payout. Matthew 5’s extra mile might hint at this: it’s not a one-off, but a posture of humility and repair.

My Thoughts

I love this angle—it’s grounded and human. You’re not claiming cosmic atonement; you’re saying, “If I’ve wronged you, I won’t fight your response—I’ll go overboard to show I’m sorry.” It fits Jesus’ radical generosity, even if the text’s original context leans toward enduring evil, not causing it. The “resist not evil” becomes “don’t resist owning my evil,” and the extra (cheek, cloak, mile) becomes your $400—a loud, practical apology.

Does that capture your intent? And what “more” do you think true repentance might look like beyond the $400?

Home > Articles > (Resist Not Evil) Do not resist an evil person? Did I read that right?